The list of evergreen aspirations, what organizations aim for with their management, is as long as it is timeless. For decades, promises like focus, transparency, customer centricity, to name just a few, have helped sell organizational changes and consulting projects.

The promoted frameworks and methodologies might change over time, the problems and aspired benefits not so much (which is why many professionals are, understandably, skeptical about “the framework industry” and the attached business interests).

To illustrate this with another example: almost every management framework promises to create what business literature calls “organizational alignment”—ensuring that everyone in the company is moving in the same direction, towards a common goal, with a shared understanding of priorities.

The benefits of achieving better alignment through the suggested framework implementation can be substantial:

- Faster execution: Aligned organizations spend less time resolving conflicts and more time executing.

- Increased efficiency: When teams understand how their work connects to strategic priorities, they make better decisions about resource allocation and focus.

- Improved employee engagement: As research has shown (see specifically Adam Grant, 2008), people are more motivated when they understand how their work contributes to larger organizational goals and when they are part of a collaborative team structure

- Greater adaptability: Well-aligned organizations can pivot more quickly when market conditions change.

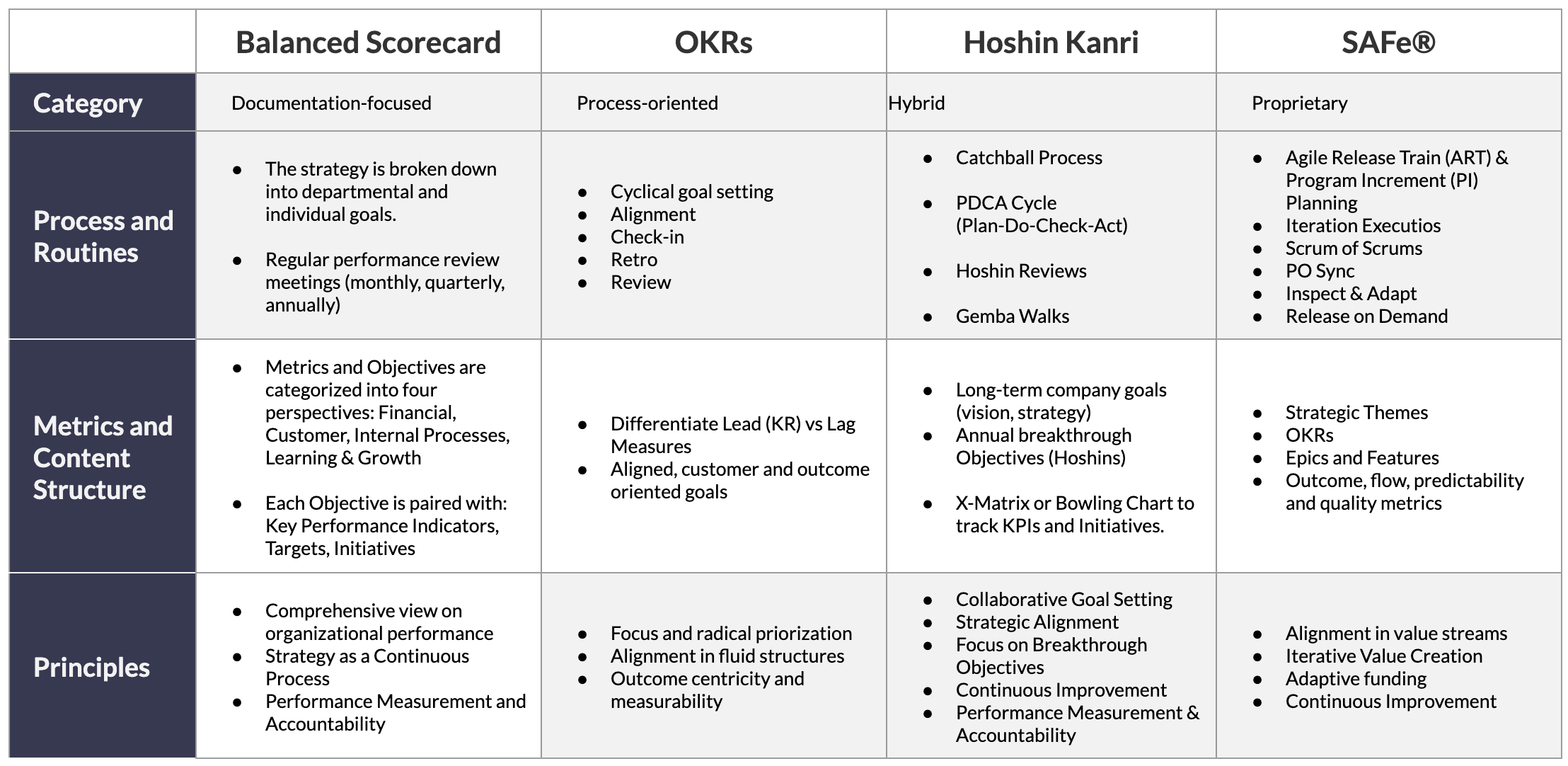

Now here is the thing: Different frameworks approach the alignment challenge through very different mechanisms—whether through visual strategy maps (Balanced Scorecard), catchball processes (Hoshin Kanri), or transparent goal hierarchies (OKRs). Implementing them unintentionally (whether teams align around outcomes, output or organizational structures can lead to very different results) or wrong, however, can sometimes create more harm than good. So understanding these different mechanisms can be crucial for selecting the framework (or framework elements) that will best address your organization's specific alignment challenges.

Note: Matching management frameworks to organizational needs should always be the first step in this decision-making process. If you haven’t already, read our guide on how to do so here.

Comparing Popular Organizational Frameworks

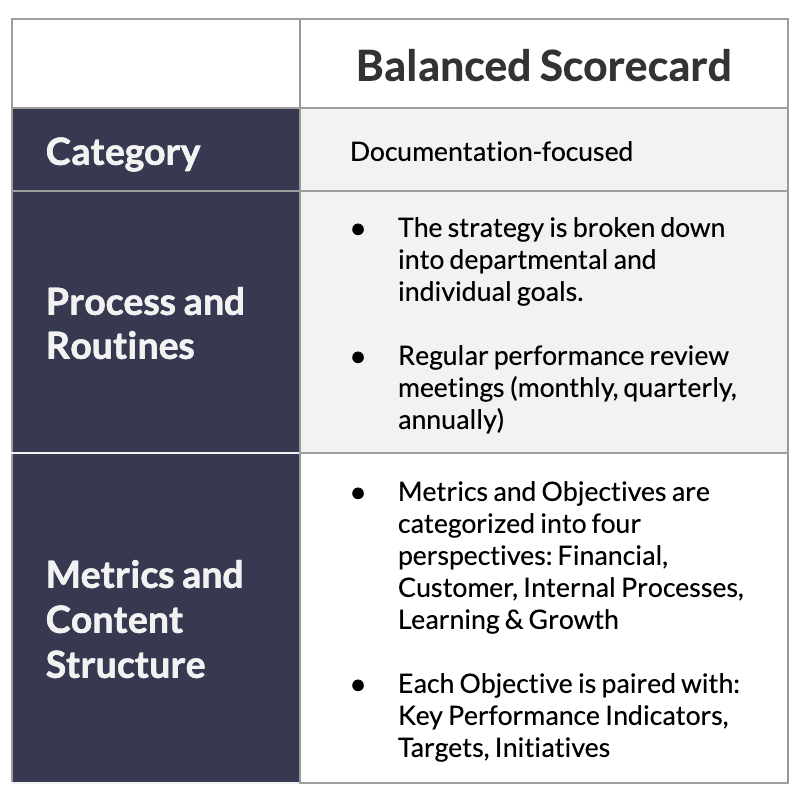

Most management frameworks can be roughly sorted into two categories: process and documentation. While many claim to provide best practices for both categories, in reality, they typically lean more heavily in one direction.

Understanding these categories can help you gain a comprehensive overview and make better-informed decisions about which approach might best serve your organization's ambitions. The goal for managers should always be to pragmatically combine elements from both categories, adjusting the focus based on their organization's needs and capabilities. There's also a clear trend emerging toward lighter-weight, more adaptive frameworks that emphasize simple, evolving processes over heavy documentation requirements.

1. Documentation-Focused Frameworks

While all common management frameworks provide process recommendations, some emphasize “what to write down” when you plan and review your priorities. Accordingly, and in contrast to the rather process-oriented frameworks (see section below), documentation-focused frameworks predominantly define the structure and quality of the information.

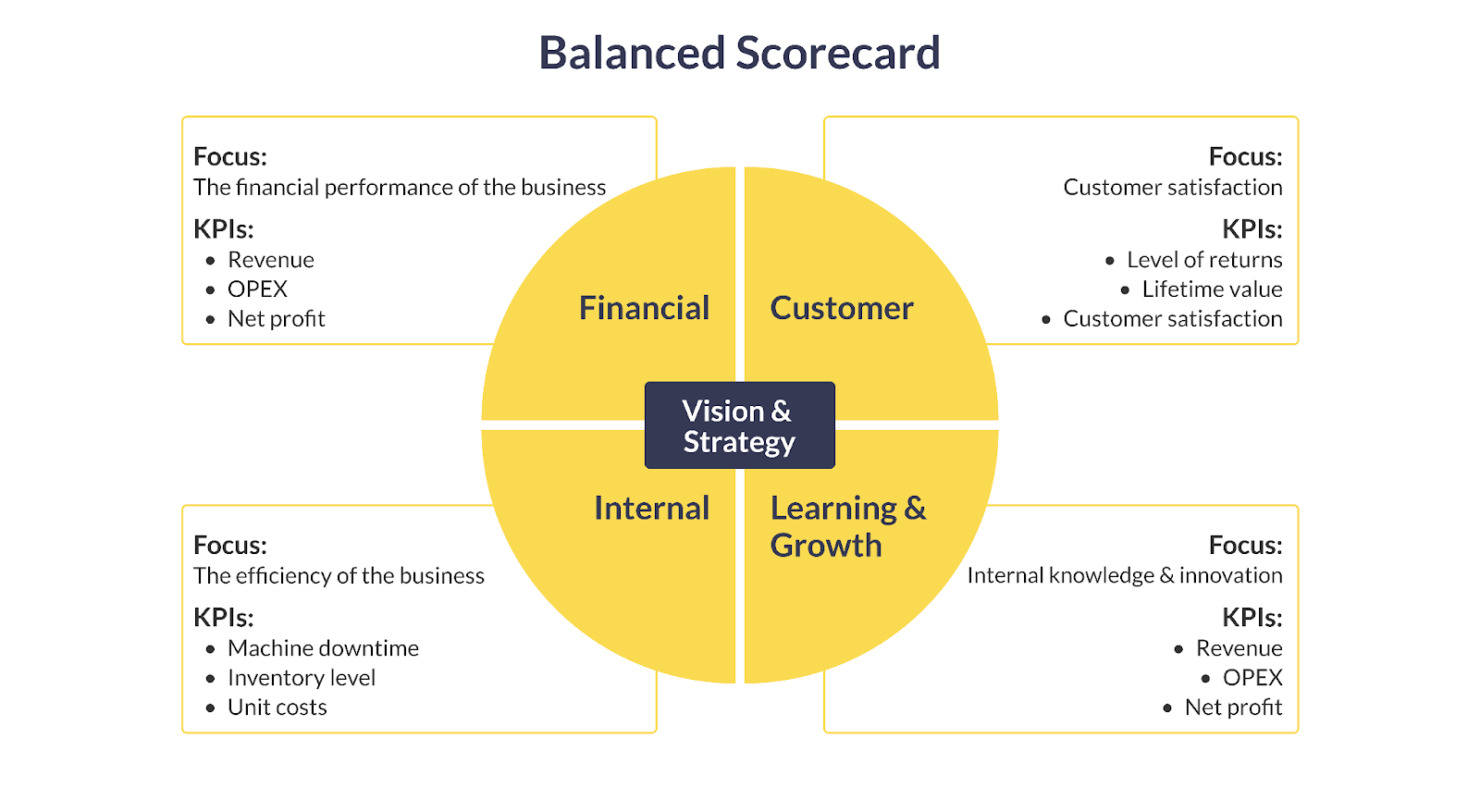

The Balanced Scorecard (BSc) is a popular example within this category. It was developed by Kaplan and Norton in the mid-1990s and emerged as a response to purely financial management approaches. It introduced a multidimensional, a more holistic and sustainable view of organizational performance across four perspectives:

- financial,

- customer,

- internal business processes, and

- learning and growth.

As Dr. Daniela Kudernatsch, a leading expert in strategy implementation frameworks, explained: “The Balanced Scorecard was about establishing a more balanced enterprise management, not just looking at financial goals, but also considering other essential factors, including leading and lagging indicators” (listen to the full conversation in Workpath’s podcast (German)). Financial metrics serve as lagging indicators (showing what has already happened), while customer, process, and employee metrics function as leading indicators (signaling what might happen).

The primary advantage of documentation-focused frameworks is their comprehensive approach to measurement. However, they often suffer from information overload. Kaplan and Norton said '20 is plenty'—meaning five goals per perspective, which amounts to a total of 20 goals at the top level.

But what happens when organizations try to cascade these 20 goals throughout their hierarchy? The math quickly becomes overwhelming: If each department creates 20 goals aligned to the company's goals, and each team under those departments does the same, you quickly end up with hundreds or even thousands of metrics that become impossible to track meaningfully, let alone manage effectively. At a certain number, KPIs do not ensure focused performance anymore and hence, stop being “Key” Performance Indicators.

While Kaplan and Norton also offered suggestions on how to work with the Balanced Scorecard, the way it has been implemented and perceived in organizations over the last decades, “it is rather a rigid documentation template that emphasizes filling forms and building dashboards, than about asking the right questions, pragmatically selecting a few focus metrics, and driving real progress”, as a Workpath customer once put it.

Luckily, there are more process-oriented frameworks which provide exactly that, while still integrating core ideas from the BSc like lead and lag measures or the four metrical perspectives.

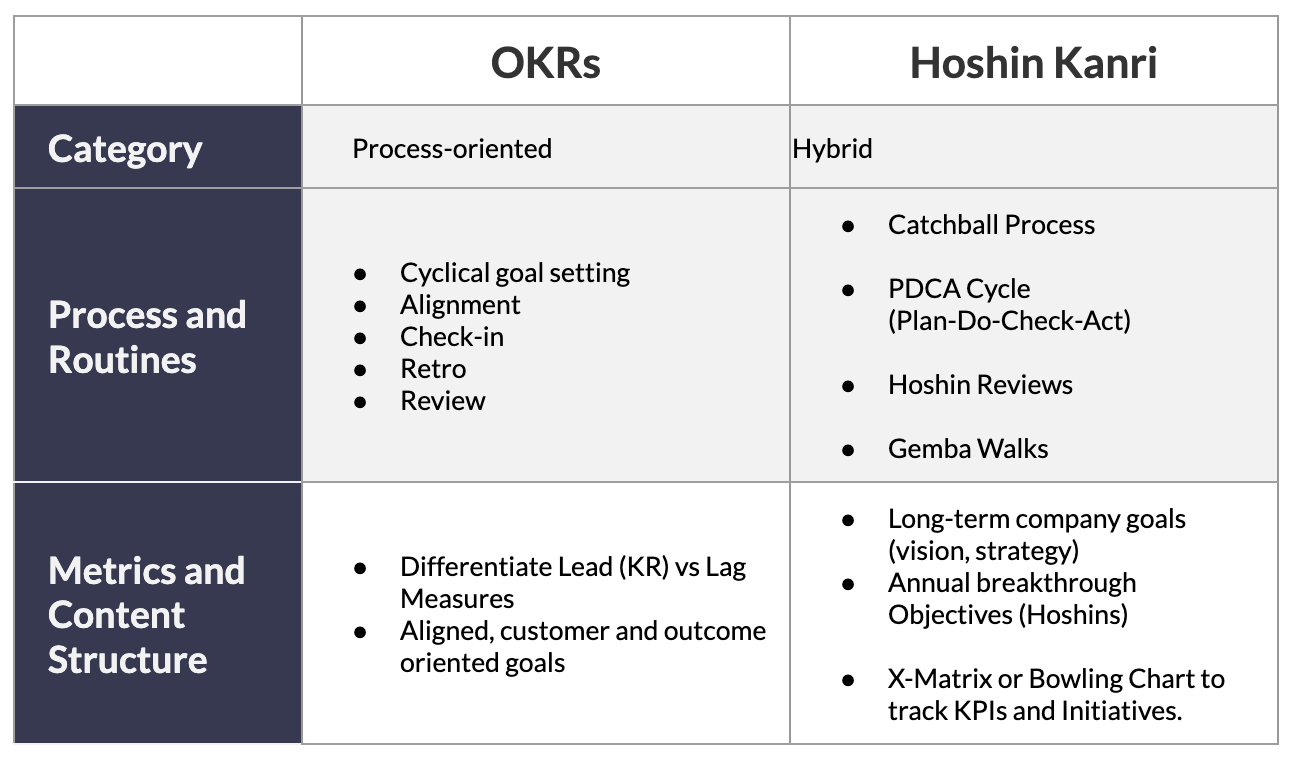

2. Process-Oriented Frameworks

Process-oriented frameworks, with the guidance they provide and the emphasis they create, focus less exclusively on the quality of the information to record (in fact, some actively try to be more light-weight and simple here) and more on the process model—who talks to whom in what order, and how decisions (for example around prioritization or alignment) are being made.

In this category, OKRs are one of the most interesting and prominent examples because while they date back to the 1970s, when Andy Grove implemented “Objectives and Key Results” at Intel with some simple ideas on the information quality (of goals), over time the framework was enriched with more and more process-oriented principles and recommendations that today dominate how OKRs are being used.

The OKR framework still centers on defining

- Clear Objectives (qualitative, inspirational goals) and

- Key Results (specific, measurable outcomes that track progress toward the objective).

What turned OKRs into such a success in the last decade, was this apparent simplicity in its structure, combined with a set of light-weight process elements that are supposed to drive speed, collaboration, and adaptability. The process typically follows a quarterly rhythm (aligned with regular business reviews, like QBRs) with regular check-ins, reviews, and retrospectives.

According to Kudernatsch, OKRs are “a very simple instrument that aims to create high transparency in companies”. Other industry leaders echo this view. John Doerr, who introduced OKRs to Google and authored “Measure What Matters,” describes them as “a collaborative goal-setting protocol for companies, teams, and individuals.” Christina Wodtke, author of “Radical Focus,” also notes that “OKRs create a rhythm of engagement that keeps teams focused on what matters most.”

Put simply, OKRs—which are ideally known to everyone in the organization—promote a more autonomous and light-weight approach to goal-setting. With OKRs, teams and employees have the freedom to define priorities from the bottom up, all in service of company goals. This differs from traditional approaches, where goals simply cascade down through hierarchical levels, resulting in long lists of metrics and initiatives that focus more on control than on fast learning and adoption. This encourages innovation and ownership while maintaining alignment with strategic priorities.

In addition, the concept of "catchball" from Hoshin Kanri illustrates how process-oriented approaches can facilitate alignment through structured collaboration rather than rigid documentation. In catchball, goals are passed back and forth between organizational levels for refinement and commitment. Unlike traditional top-down approaches where goals simply flow downward, each organizational level actively develops their own solutions and implementation plans. These plans are then 'played back' to upper management for feedback and refinement. This collaborative process helps teams shape goals that are meaningful and actionable in their context, leading to stronger buy-in and ownership.

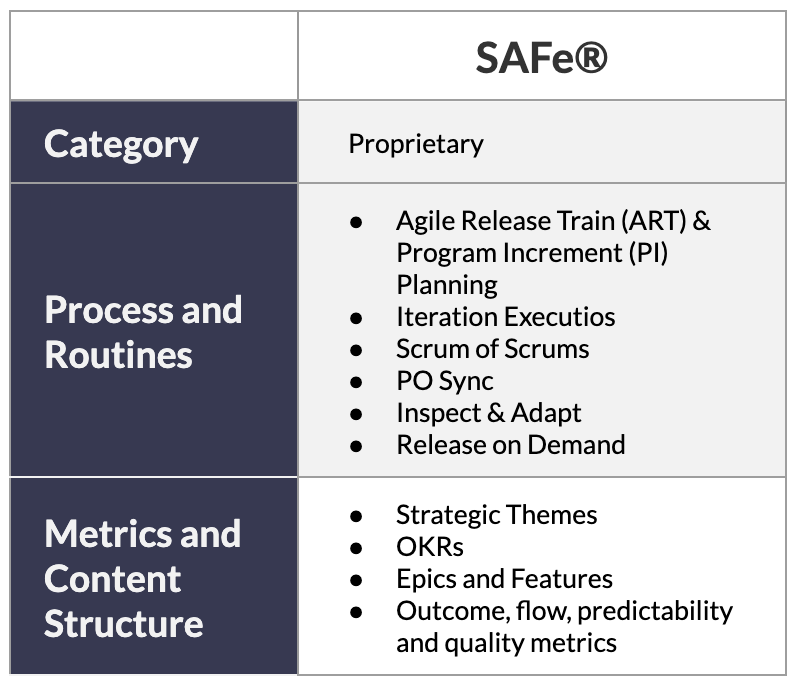

A note on proprietary vs. open-source frameworks

Some frameworks, like SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework), are trademarked products and come with specific certification and implementation requirements. Others, like OKRs, are rather open-source in nature, allowing for more flexible adaptation to your organization's needs and cost-saving in the implementation

The open-source nature of frameworks has led to significant variation in implementation. When OKRs are mentioned in one company, you should not assume they mean the same thing as in another company. We see various manifestations in our daily work, such as OKRs for personal goals, or worse, OKRs simply as a label for old school target agreement and HR performance management processes, where nothing really changes procedurally or culturally and hence little positive impact can be experienced.

Proprietary frameworks, on the contrary, may be less adaptable to your specific context but often provide more structure and support. They typically come with not just higher implementation costs because of the required training and certification, but also with less flexibility and autonomy for the organization to evolve with the process over time.

Shifting from Process to Principles—A Personal Perspective

After years of helping organizations implement management frameworks and processes at scale, I am suggesting a shift in how we approach these changes in methodologies and operating models – a shift that luckily has begun to emerge already. The established, old approach is prescriptive: follow these exact steps, use these specific templates, hold these particular meetings. But time and time again, I've seen organizations faithfully follow every procedure yet fail to unlock the value they were seeking.

Successful framework implementation isn't about rigidly following procedures, and rules—it's about understanding and embedding new principles and the ways of working that serve your organization on its trajectory and in the context of your goals.

When organizations treat frameworks as rigid prescriptions, several problems typically emerge:

- Teams focus on completing templates rather than having meaningful discussions.

- People follow processes without understanding their purpose, unable to identify why they might struggle or how to adjust the process.

- The framework becomes a bureaucratic burden rather than a tool for better decision-making and collaboration.

- Organizations struggle to adapt the framework when circumstances change.

In contrast, when organizations focus on understanding and applying core principles, they can ensure more flexible, effective, and sustainable implementations that make the new framework feel like a strengthening backbone for their business, not like a fake skin or a heavy burden on their shoulders. Looking at the frameworks discussed so far, here’s a list of their core principles (what they are known for) that can be integrated and combined as valuable building blocks in almost any kind of operating model:

Balanced Scorecard:

- Balance between short-term and long-term objectives

- Integration of leading and lagging indicators

- Clear line of sight from strategy to operations

- Holistic view of organizational performance

OKRs:

- Focus and prioritization

- Transparency and visibility

- Shorter planning and review cycles for fast adaptation

- Balance ambition and achievability

- Cross-functional alignment

Hoshin Kanri:

- Collaborative goal-setting

- Two-way communication across levels

- Focus on breakthrough objectives

- Integration of strategic and daily management

The key to successful principle-based implementation is to treat each principle as a design guideline for your process or operating model rather than a rule to follow. For example, when facing a choice about how to structure goals effectively, instead of asking “What does the framework manual say?” ask:

- Does this approach promote transparency?

- Does it help us to think about customer value first, when we plan?

- Does it enable meaningful alignment?

- Will it help teams focus on what matters most?

- Can we adapt it as circumstances change?

This principle-based approach requires more judgment and leadership than following a prescription, but it ultimately leads to more sustainable and effective implementations. It also allows organizations to combine elements from different frameworks in ways that make sense for their specific context.

Moving Forward: Beyond Framework Selection

Navigating the framework jungle can be frustrating, with each approach promising to be the superior solution, and other approaches already somehow living somewhere in the organization. But as we've explored, the key to success lies not in choosing the “perfect” framework, but in understanding how different approaches serve different needs:

- Documentation-focused frameworks like the Balanced Scorecard excel at providing comprehensive measurement systems but require careful management (and the occasional cleansing) to avoid metric overload and documentation fatigue

- More Process-oriented frameworks like OKRs offer flexibility and simplicity, but need cultural support to be adopted as well as quality management on the information quality nonetheless

- The best operating models are able to integrate useful elements from both categories, encouraging pragmatic but precise planning, rigorous but effortless (ideally automated) monitoring, and continuous adjustments through short cycles.

So rather than treating these frameworks as competing alternatives, consider them as a toolkit of principles and practices. Ask yourself: What problem are you really trying to solve? What is your organization ready for? How will you ensure sustainable implementation?

The most successful organizations aren't those that perfectly implement a single framework—they're the ones that understand the principles behind different approaches and thoughtfully adapt them to their context. As you move forward, remember to:

- Start with principles, not processes

- Adapt with purpose, not just for convenience

- Measure what matters, not just what's easy

- Build capability continuously, not just during implementation

In the end, frameworks are tools, not solutions. Your success will come not from the framework you choose, but from how well you understand and apply its principles, to build a better operating model that can create superior results.

Literature

Grant, A. M. (2008). The significance of task significance: Job performance effects, relational mechanisms, and boundary conditions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 108–124. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.108

%20(1).jpg)