“We've tried it all: Balanced Scorecard, MBO (Management by Objectives), Hoshin Kanri, OKRs. But eventually, they are all kind of similar, and nothing seems to really work for us.”

Does this sound familiar to you? If so, you are not alone.

Conventional wisdom says that framework implementations mostly fail due to a lack of buy-in and poor communication. Yet, many organizations still approach framework implementation like following a strict recipe: pick a framework, follow the prescribed steps, and expect results. The truth is, this—sometimes almost religious—adherence to framework orthodoxy can be the real culprit.

The most successful organizations don’t just bend playbook rules; they adjust the frameworks to their organization and implement them in a much more iterative way, with a more long-term perspective. They treat frameworks more like guardrails and tool boxes, consisting of modular solutions—taking what works, discarding what doesn't, and over time developing a unique approach, tailored to their needs. Some even deliberately combine frameworks to increase acceptance, satisfy a range of stakeholders, address different levers of their strategy execution, and ultimately come to an operating model that serves their ambitions.

The Underestimated Relevance of Integrating and Combining Management Frameworks

Treating any management framework as a standalone solution—as “the latest one-size-fits-all silver bullet to replace all prior approaches”—is a common mistake. The reality we've observed across hundreds of implementations is different: the organizations that succeed deliberately combine, integrate, and harmonize frameworks to address different aspects of steering their business. On the one hand, this better addresses the corporate reality of different, already existing frameworks, and hence can drive acceptance and adoption. On the other hand, it allows them to pick proven mechanisms and solutions, combining them in a “best of all worlds” operating model for their very individual goals and challenges.

While there are, of course, caveats and pitfalls to this best practice, which we will address in the next section, we have experienced plenty of great examples validating the approach.

An automotive supplier we work with, for example, combined Hoshin Kanri with OKRs. While the Hoshin Kanri process has been in use in some units for more than seven years, establishing “breakthrough priorities” and ensuring cross-functional alignment, OKRs provided more focus on measurable and customer-centric planning, new cadence, and focus on quarterly execution. Picking up on the simplicity of OKR goals, replacing some of the more extensive planning templates from their old processes, this also offered the opportunity to streamline Hoshin Kanri and make it less of an annual bureaucratic effort, and more of a ritual that is always present and guiding faster course-corrects in everyday work.

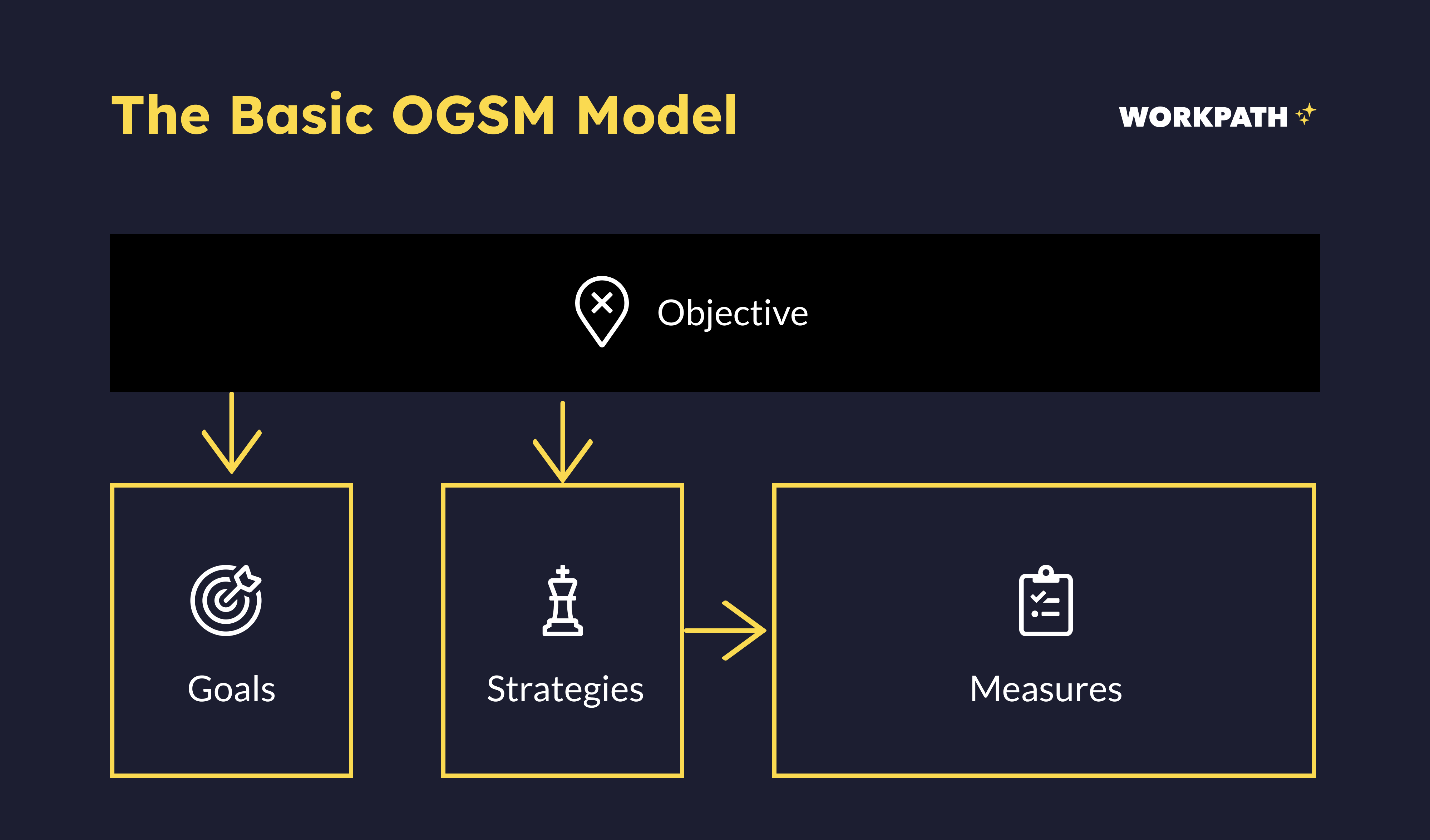

Another customer, in the energy sector, added a simplified variation of OGSM (Objectives, Goals, Strategies, Measures) to an established Balanced Scorecard system to create a more dynamic execution layer. The existing Balanced Scorecards provided comprehensive measurement categories, structuring focused key metrics and providing guidance for a more aligned goal setting process, while team Objectives and Goals drove focus and execution on quarterly priorities. The combination helped address the common Balanced Scorecard challenge of connecting strategy to day-to-day execution while maintaining the benefits of its comprehensive measurement approach and KPI system.

As a third example, a large service and consulting unit within an international airline group iterated on its integration of OKRs within SAFe. While OKRs are officially part of the widely adopted SAFe framework already, the advantages of OKRs are oftentimes constrained by the complexity and regulation overload of SAFe. Hence, the service unit decided to simplify some of the SAFe planning formats and provide more autonomy to teams, ensuring that OKRs maintained their simplicity within the more complex SAFe environment, but also allowing OKR goal setting where SAFe would not have prescribed it. That way, the organization, for example, ended up using top-level OKRs for alignment in its portfolio configuration, while not implementing OKRs across all levels.

Why Most Framework Implementations and Integrations Fail (Plus: How to Make Yours Different)

- Framework and Reporting Overload

Additive Bias is one of the most common—and most challenging—patterns for managers today. The instinct to keep adding new steering elements or frameworks often backfires. Without removing or simplifying existing processes, new frameworks create redundancies, bureaucracy, and resistance. As noted in previous publications, “A new framework should never feel like just another layer; it should change and improve existing processes or even replace them completely.” Start by unbundling current approaches, distilling them to their essentials, and then reassembling them into a single, effective operating model. - Conflicting Terminologies

Different management schools and frameworks use similar terms to describe different things (e.g., “objectives” in OKRs versus MBOs) and vice versa. Establish clear, consistent terminology and leadership communication for your integrated approach. While it is recommended to leave teams with flexibility and autonomy in how they work, we advise centrally defining strict standards with regard to terminology in shared processes. Also, it can be beneficial to acknowledge the internal history of the language in use: if a process, for example, is “burned” or less popular, replacing it and its keywords can be an opportunity. - Framework or “Operating Model” Implementation as a Political Play

Whenever a new leader takes charge, a familiar routine often unfolds: they share 100-day plans, “thoroughly analyse” the status quo, and soon introduce new processes, templates, and tools. While this can make sense, it often marks a breaking point for employee engagement and effective execution. Many new managers rush to show action and fast change, ignoring what already works or has just started working. The most successful managers resist letting ego or symbolism drive their first 100 days. They deliberately decide what to stop, what to change, and what to maintain — and they communicate those decisions clearly. - Misaligned Cycles

For larger organizations, it is normal to have a multitude of rhythms and cycles on different levels of the business. Fiscal years might differ from calendar years; the “winning plan” routines of board area A follow a tertiary rhythm, while the people strategy that involves teams from all board areas has to be adjusted and reported on a quarterly basis. Hence, as difficult as it might be, it is important to ensure clarity on the different cadences and aim for a synchronization of different planning and alignment processes (including their frameworks). For example, annual Hoshin Kanri planning should feed into quarterly OKR cycles in a coordinated fashion, and planning output in project management should not come long before planning outcomes in quarterly OKRs. - Disconnected Conversations

Without conscious integration, different frameworks may fail to uncover and resolve competing priorities. Ensure that the key conversations (about input, output, outcome, and impact decisions) from different frameworks are connected and can ensure alignment to overarching strategic north stars. For example, linking portfolio planning meetings with mid-level OKR announcements helps create clearer connections between outputs and outcomes, reducing resource waste and avoiding misalignments. - Clear Operating Model, Purpose, and Vision

The absence of a clear purpose and vision for the organization’s (new) ways of working often leads to confusion (“Why change? Where are we heading with this?”) and rejection. Ensure that framework introduction and integration efforts follow a clear organizational vision that explains why the changes are necessary and how they will benefit not only the organization but also its teams and individuals. - Skills and Capability Gaps

Without the right skills, implementing or integrating a framework triggers anxiety and avoidance. New management frameworks demand new capabilities, and a book or short training rarely suffices. Many professionals in large enterprises have never learned to set customer- and outcome-oriented goals that show measurable value creation rather than just project output. Introducing frameworks like OKRs requires ongoing skill building. Organizations must invest in both technical know-how and core capabilities, such as strategic, customer-focused thinking and KPI literacy, so teams can confidently define measurable targets on their own.

Making It Work: A Practical Implementation Approach

Successfully implementing framework combinations requires a comprehensive approach built on three pillars:

- Understanding the underlying principles of the framework(s) at hand

- Investing in the capabilities that enable framework adoption

- Integrating with adjacent business processes and systems

1. Understanding the Essential Principles of the Framework(s) at Hand

Whatever framework or combination you choose for your operating model, focus on adapting it to your organization rather than applying it strictly by the book. Consider your specific context—strategy, culture, industry, and current trajectory—and shape ways of working that fit these realities.

Therefore, start by unbundling existing and potential new approaches, stripping them down to their core elements. This will put you in a position to reassemble a model that is fit for purpose, making conscious and confident design choices that match your challenges and ambitions.

If you skip that first step, you might blindly follow playbooks that do not work for your culture, and create redundancies, confusion, and rejection. Common examples in companies that made this mistake are:

- Two or three different priority announcements that present misaligned or ambiguous top-level goals

- Reporting templates and meetings covering almost the same topics but with slight differences, creating extra work and additional discussions

- “Fake planning sessions” where other processes have already set the course earlier in the cycle, yet teams are still expected to plan for themselves

There are different approaches to unbundling and reassembling “fit for purpose frameworks” from their building blocks, but two perspectives we find particularly helpful in our work with organizations:

First, it makes sense to evaluate and structure framework components by the principles and behaviors they promote, especially the ones that might interfere with a company’s culture. When integrating different (e.g., existing and new) approaches, it helps to acknowledge that each organizational design choice bears trade-offs with benefits and costs. By comparing the building blocks of different frameworks as suggested here, you can identify mismatches and discuss with your team which design choices will better serve your goals.

The following examples illustrate how you can map and compare framework elements by the behaviors and principles they promote:

- Centralized vs. decentralized: Do you need fast, efficient, top-down planning, or a more decentralized approach that is closer to customers and more engaging for teams?

- Communication vs. documentation (and their frequency): Do you want teams to update each other weekly to learn and adjust faster, or are quarterly calls enough — more efficient and report-oriented, but less connected to ongoing developments in a volatile environment?

Further, oftentimes closely connected, dimensions: What level of transparency do you need? Should you prioritise stability or agility, efficiency or effectiveness, and how will you balance the trade-off between security and speed?

Once you have mapped framework elements along these dimensions and discussed trade-offs as well as design preferences, you can pick and combine the ones that work best for you and the organization’s goals.

The second complementary approach to unbundling and reassembling frameworks looks at the nature and quality of their planning artifacts. It untangles them with the question of what exactly needs to be planned in which step, differentiating between resource input, work output (and activities), outcomes (or value for a certain stakeholder, driven by the inputs and outputs), as well as business impact. Different frameworks naturally emphasize different parts of this chain:

- Balanced Scorecard provides comprehensive measurement across the entire chain, but with a stronger focus on financial impact and customer outcomes. However, most organizations lack a functioning feedback loop between these metrics and the initiatives and investments that drive them.

- Hoshin Kanri strengthens the connection between breakthrough objectives and tactical initiatives. However, its X-matrix is often seen as too documentation-heavy to work as an everyday communication tool—one that is updated frequently and sparks meaningful discussions along the way.

- OKRs focus primarily on aspired outcomes, measured by leading indicators, and on the support provided by contributing projects (outputs). However, they are somewhat ambiguous about how to integrate with KPIs and traditional business impact metrics, so organizations need to define that interface themselves.

By implementing a new approach or integrating different frameworks through this lens, you can manage the entire impact chain in a holistic and seamless way, avoiding disconnected or even contradictory measurement systems and decisions. This alignment is crucial to:

- Avoid redundant or conflicting priorities and metrics

- Ensure resources flow to the most important strategic priorities

- Create a clear line of sight from day-to-day work to strategic impact

- Maintain focus on both short-term results and long-term value creation

- Establish short feedback loops between elements of the impact chain

2. Invest in the Capabilities that Enable Execution

All the efforts for a new implementation or an operating model update can only be fruitful if built upon the required organizational capabilities. These capabilities represent the “muscles” an organization must develop over time to fully leverage the benefits of the new approach, regardless of which frameworks were chosen.

Numerous implementations have shown how much organizations frequently underestimate these capability requirements, assuming framework adoption is primarily about process design rather than employee enablement and organizational readiness.

In previous publications and webinars— like in my conversation with BCG’s partner Jan Wulff—we have already discussed some of the key capabilities organizations need to build in order to implement and execute future-proof operating models:

Clarity of direction: Alignment on all levels via clear chains of outcomes, goals, and business impact

Frequency and quality of decision making: Quarterly business reviews, outcome-driven planning, and continuous measurement

Flexibility of funding: Top-down allocation of funding and resources aligned with an outcome-centered portfolio

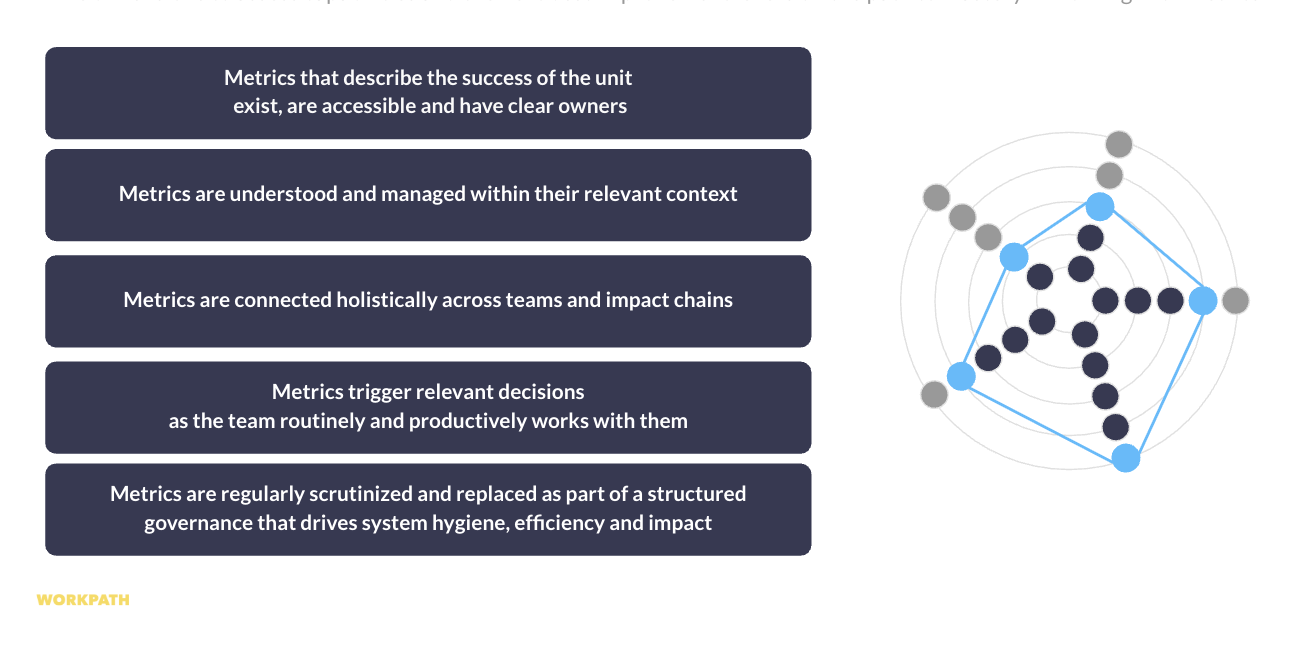

KPI Literacy: Effective use of any framework requires access to the right information systems as well as the ability to work with data (turned into measurable insights and performance indicators).

Even though many of these capabilities might seem basic, a lot of organizations still are not there yet, ensuring:

- Metrics that describe the success of the organization and of every unit exist, are accessible, and have clear owners

- Metrics are understood and managed within their relevant context

- Metrics are connected holistically across teams and impact chains

- Metrics trigger relevant decisions as the team routinely and productively works with them

- Metrics are regularly scrutinized and replaced as part of a structured governance that drives system hygiene, efficiency, and impact

Take the KPI Mastery (Self) Assessment to evaluate your organization’s maturity and identify development opportunities as well as low-hanging fruits for improvement.

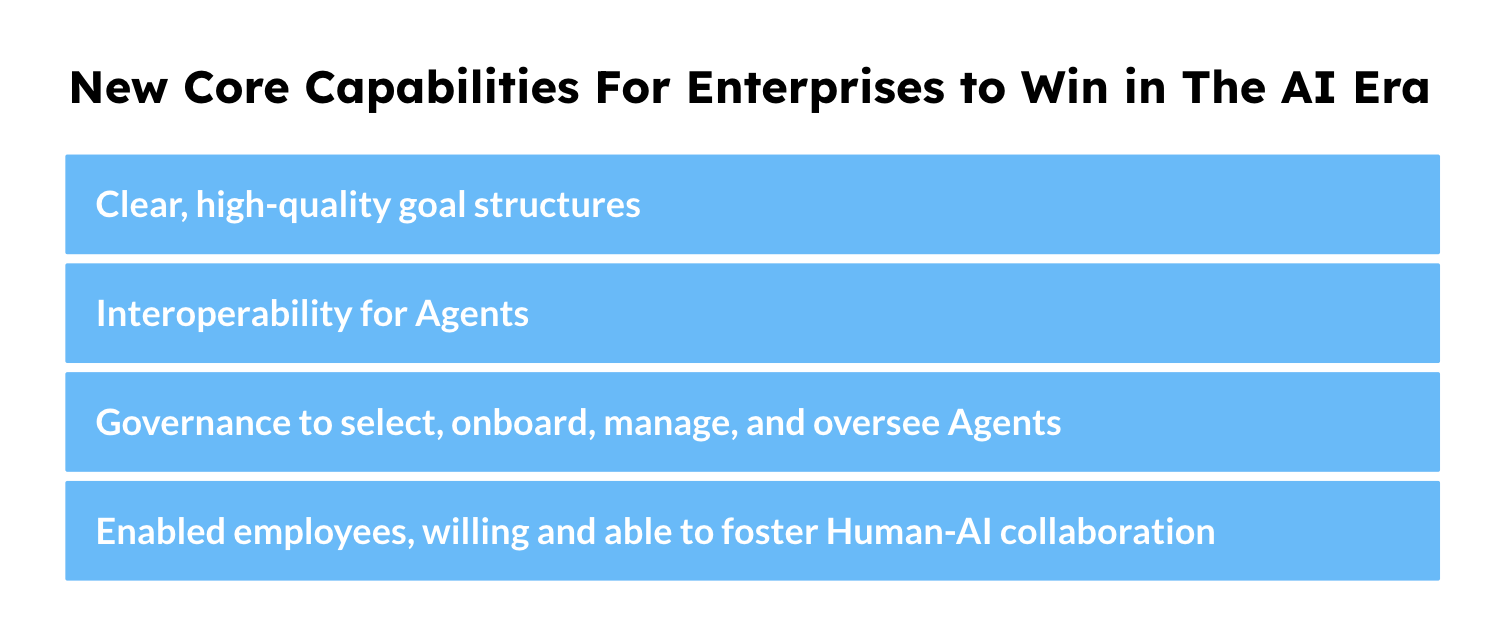

AI Literacy and Infrastructure: The first movers in strategy execution already use AI Agents embedded in their tools. They speed up onboarding for new frameworks, support goal-setting, and give teams feedback to improve planning and alignment. What once needed long training and expensive coaching now happens continuously, on the job, and at scale.

AI Agents are also changing who plans and who executes. Mixed human-AI teams are emerging, with AI handling more complex tasks. To succeed, organizations need:

- The right technical infrastructure

- Managers who can work with AI

- AI literacy across all employees

- The ability to treat AI Agents as “digital employees” – selecting, managing, and improving them

- These capabilities will define whether operating models stay competitive.

If you are interested to learn more about the capabilities enterprises require to win in the AI era, we recommend you to read this related article.

The development of the required capabilities we describe above cannot be rushed. Based on the experiences from our consulting practice, the enterprises that dedicate sufficient time (at least 6-12 months) to developing these foundational capabilities report significantly higher long-term success rates than those that only think about capability-building during or after a full-scale implementation.

However, framework implementation and integration is not only a matter of employee adoption—it also is about an effective incorporation into your organization's existing operating model as well as the adjacent steering and collaboration processes. Without integration, any new framework is at risk of remaining an isolated and toothless initiative, disconnected from core business operations and decisions.

3. Integration with Adjacent Systems and Processes

Our research reveals that organizations achieve 3-4x higher adoption rates when frameworks are deliberately harmonized with and woven into existing business systems rather than allowing them to operate in parallel, in a more disconnected manner. Key areas and process categories where integration is critical:

Performance Management Integration

Frameworks like OKRs often face resistance when their relationship to performance evaluation remains unclear. While many experts recommend keeping OKRs separate from compensation decisions, they shouldn't exist in a vacuum. The most successful organizations maintain this separation while creating deliberate touchpoints between team-oriented strategy execution and performance management processes.

A global consumer goods company, for example, maintains OKRs as a strategic steering and alignment tool while using its existing performance management system to evaluate employee contribution. Managers conduct quarterly “alignment conversations” that loosely reference OKR progress over several cycles as context for performance discussions, without directly tying bonuses to OKR achievement. The organization repeatedly explains (on a quarterly basis) how OKRs are supposed to encourage experiments and ambitious short-term team goals (that might sometimes fail), while performance is rather evaluated based on an individual’s role description and their development over a longer period of time.

Furthermore, enterprises should document how the new framework relates to performance reviews, promotions, and compensation. Managers should be trained to explain the purpose of the different processes and keep their mechanisms separated, as intended.

Budgeting and Resource Allocation

Most corporate budgeting and portfolio management processes are decisive mechanisms that define an organization’s investment priorities and direction. After all, decisions around who gets headcount and budget still dominate the perception of strategic relevance and political power.

Hence, any other management framework that intends to facilitate goal setting and prioritization has to be integrated to inform resource allocation decisions. Otherwise, “important goals” might be prioritized (e.g., in a new OKR process) but never get funded, because other priorities were already set in the annual portfolio process. The goal-setting process may still improve focus and alignment across teams but largely remains toothless.

An effective integration of corporate goal setting and resource allocation creates seamless “chains of why” – or, as we at Workpath call them, “input-output-outcome-impact chains.”

A future-proof integration today, best case, allows for dynamic resource reallocation (that is, the budgeting process enables resource shifts based on insights from the more iterative and continuous goal-setting process) and transparent funding decisions by connecting strategic priorities and resource allocation.

A good first step towards a better integration is to incorporate framework output (e.g., previously defined priorities) in budget templates and resource request forms, and to establish regular review points (quarterly is most common) where resource allocation gets evaluated by its impact. Also, leading organizations in that context create “strategic investment pools” that can be rapidly deployed to emerging opportunities identified through the framework. Last but not least, we also recommend mapping the annual budgeting process and its timelines against your framework cycles to identify possible synchronization points.

Project and Portfolio Management

Oftentimes closely connected to budgeting, most organizations have well-established processes to define their portfolio of initiatives and projects (usually very output-oriented).

The disconnect between strategy-cascading management frameworks and operational project management often creates a critical gap. Legacy portfolio processes define clear input-output projects, but their impact on customer value (outcomes) and business metrics usually stays unclear and unchecked. As a result, funded projects often lack leading measures to evaluate early whether an investment truly drives value.

This gap can be bridged by ensuring projects feed into strategic goals, while strategic shifts inform project priorities (bidirectional alignment) and creating governance mechanisms that assess projects against the overarching framework priorities. After all, also from a project and portfolio management perspective, you want to ensure you get closed and manageable input-output-outcome-impact chains.

Further Integration Areas

Beyond these examples, a successful framework should consider:

- Operational Processes: Ensure day-to-day decisions stay informed by the priorities defined in your planning framework (e.g., Hoshin Kanri or OKR)

- Systems and Tools: Connect all data that is relevant for working with your planning framework with existing enterprise systems for seamless information flow

- Talent Development: Integrate the capabilities needed to excel within your operating model and its frameworks into your skill catalogue and employee development programs (e.g., in your Learning Management System)

The goal should be to create a coherent operating model where your management frameworks enhance rather than complicate existing operations. Each integration point should reduce friction, erase redundancies, and improve decision-making rather than adding an administrative burden.

Looking Ahead: Building Competitive Operating Models for the Future

The most successful organizations of the future won’t be the ones who comply best with given frameworks. It will be the ones that can constantly adjust their own operating model to their context and goals.

Volatility and dynamism will further increase, so adaptability not just of businesses, but of their ways of working will become critical. In that environment, neither the most agile nor the most stable, nor the most efficient nor the most effective organization wins - but the one that can move swiftly between the ends of these spectrums, while continuously serving the customer, as the environment and its respective demands change.

Most frameworks, and even more so, the way corporates today work with them, are too rigid for that future reality after all. Tools and frameworks might provide deceptive security and stability, but they cannot replace independent thinking, critical discussion, productive conflict, and accountability in leadership teams.

Winning organizations in the future will be driven by small, accountable units with high levels of autonomy that can define their ways of working based on shared principles, but within clear guardrails. Run by empowered employees who are trained to adapt and operate within a more fluid operating model. They will be supported by a growing number of AI Agents that will take over increasingly complex tasks. These Agents have strict requirements, like clearly defined and accessible priorities, as well as regular feedback and workflow access - but they will also allow their human colleagues to focus more on strategy work and on developing the organization’s performance architecture (working on the system, not just in the system).

%20(1).jpg)